| Address | 2-2-1 Wakakusa-cho, Shiraoi Town (located in the Upopoy Gateway Square) |

|---|---|

| Phone | 0144-85-2177 |

| Opening time | Same as Upopoy |

| Closing time | Same as Upopoy |

| Wi-Fi | Can access Upopoy’s free Wi-Fi |

Café RIMSE is located in the Upopoy Gateway Square. It is operated by the Hope Frontier Social Welfare Corporation, with representative Minako Tayu as the store manager.

Café RIMSE is the only place aside from Pirasare where you can eat ohaw without a reservation!

There are many items on the menu, but in this article we will explore those related to Ainu cuisine!

Contents

Ohaw

Ohaw is a traditional Ainu soup, also known as sanpei-jiru in Japanese. The staff at the Ainu Museum (the forerunner of Upopoy) taught me how to make it. At Café RIMSE we serve cep ohaw, which is made with salmon, and kina ohaw, which is a vegetarian version.

●Kina ohaw (ohaw with deep fried tofu and vegetables) set meal

Kina ohaw and sticky millet are served with konpu sito, sides, rataskep, pickles, and wild grass tea.

Kina: vegetables, wild vegetables

Rataskep: A dish made from boiled and mashed ingredients. Café RIMSE’s rataskep includes pumpkin, adzuki beans, kelp (called kombu in Japanese), and sikerpe (Amur cork tree seeds)

Konpu sito: Dumplings (sito) with kelp (konpu, called kombu in Japanese)

To make our konpu sito, we use a method that we have learned from Ainu people in the Hidaka region. Kelp is deep fried, shredded, and then mixed with a thick sauce made with ingredients like brown sugar and soy sauce.

●cep ohaw (ohaw with salmon) set meal

Cep ohaw and sticky millet are served with konpu sito, sides, rataskep, pickles, and wild grass tea.

Cep: fish. Café RIMSE uses salmon.

Pene emo in red bean soup

Pene emo is an Ainu dish that contains dumplings made from frozen potatoes.

It is served with wild grass tea and pickles.

I really liked this one, and so did my son, who guzzled it up happily!

I’m glad to hear it!

Like other dishes, our pene emo is based on the methods I learned from the staff at the old Ainu Museum.

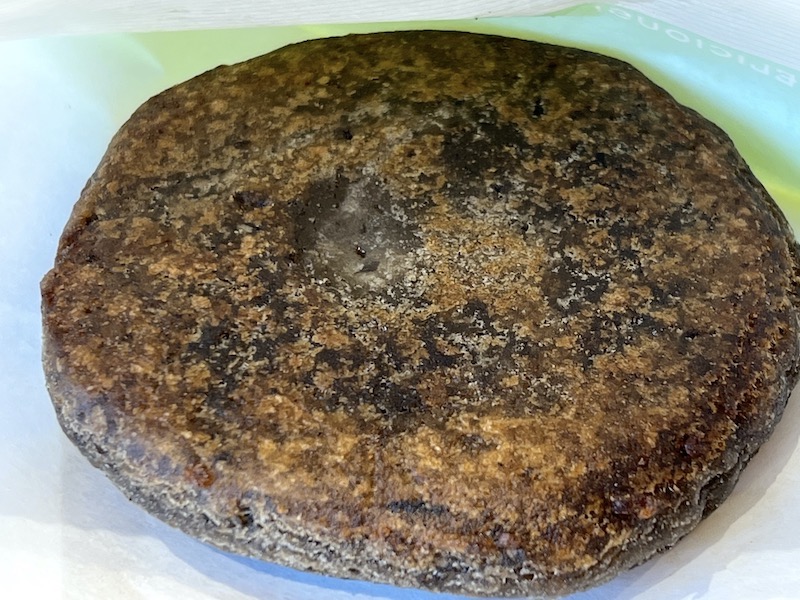

Pene emo

Pene emo is less sweet when it’s served without the red bean soup.

I really enjoy this one for its unique aroma!

The generous portion is also filling.

Some people may be surprised by the black color. This is because we freeze the potatoes many times in order to ferment them.

Pene emo used to be a hallmark of spring because our ancestors would make them as the snow melted.

Yuk cutlet curry

We make our yuk (venison) curry with venison from Shiraoi.

It’s served with salad, pickles and wild grass tea.

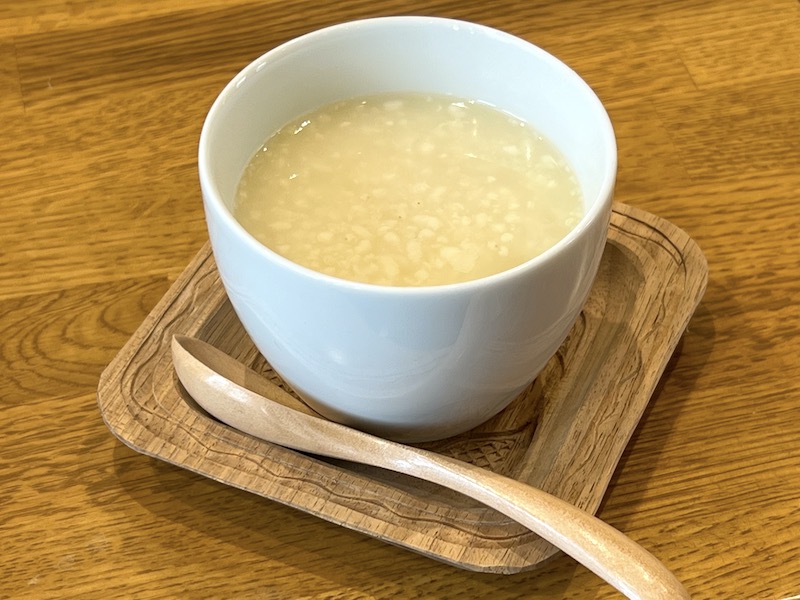

Piyapa (Japanese millet) amazake

Our amazake is healthy as it is only made with two ingredients―Japanese millet and malted rice.

To stay true to Ainu food culture, we don’t use additives or sugar.

What? There’s no sugar in it!?

It’s so sweet though!

Very tasty!

The sweetness comes naturally from the Japanese millet and the malted rice.

Japanese millet is known as Piyapa in the Ainu language.

The amazake we serve was developed by Tanaka Sake Brewing in Otaru based on Ainu food culture, with the cooperation of the National Ainu Museum.

Kamuy (spirit deity) tonoto (sake)

Tonoto is sake that is given as an offering to kamuy and Ainu ancestors, and is an integral part of Ainu rituals.

As part of a project to revitalize traditional Ainu sake, Tanaka Sake Brewing modernized tonoto under the supervision of the National Ainu Museum.

Tapestry of Ainu embroidery

The patchworks on the wall featuring embroidery of Ainu patterns are stunning!

These were made by Kyodai Patchwork no Kai, a group that aimed to bring people together by creating a giant patchwork.

.Modern Ainu cuisine

Has Café RIMSE been around since the days of Porotokotan, the predecessor to Upopoy?

Yes, that’s right. Originally, Café RIMSE was managed directly by Porotokotan, but in 2014 Hope Frontier Social Welfare Corporation took over the reins.

Under the new management, the team learned how to make ohaw from the Porotokotan staff.

When Porotokotan became Upopoy, the team at Café RIMSE joined in on an Ainu cuisine workshop that was held at the time.

At the workshop, there were demonstrations on how to make Ainu food, tasting sessions, and lectures on Ainu cuisine.

Based on everything we had learned, our head cook tweaked the traditional recipe and created an ohaw to suit a variety of palates, which can be enjoyed at Café RIMSE today.

Just as Japanese cuisine changes with each generation, so does Ainu cuisine. These shifts are also playing out in the homes of Ainu families, where Ainu cuisine has been passed down from generation to generation.

I’ve heard that some families add rice flour or pancake mix to pene emo, which was originally made with potato flour, right?

We want to recreate the traditional flavors, but we also want to create dishes that anyone can easily enjoy. So, it’s often a struggle to find the right balance between those two factors.

I think this balancing act is not limited to Ainu cuisine; we see the same thing with Ainu embroidery and rituals.

To give an example from Japanese culture, it’s like the question of how to make noh and kabuki appealing to young people.

I guess this balancing act is something many cultures are grappling with.

タント•タンタ•シラオイ

タント•タンタ•シラオイ

[…] 作品は今でも、コミセン、グランマ、東町ハウス、カフェリムセなどで展示されています。 […]

[…] お手頃にアイヌ料理を楽しみたいなら、カフェ・リムセ。 […]

[…] ポロニは、ウポポイのエントランスにあるカフェ・リムセの姉妹店です。 […]

[…] ウポポイのエントランスにあるカフェ・リムセの姉妹店でもあります。 […]